Weekly Newsletter - October 1, 2021

The Virtues of Not-Knowing

Many of us know the story of the Oracle-priestess of Delphi, who, asked to identify the wisest man in Athens, named Socrates. For Athenians, this was a bit of a Hellenistic head scratcher: why assign such an honor to the pug-nosed (and pugnacious), rabble-rousing unemployed war veteran, at a time when the upper echelons of Athenian society offered many highly regarded scholars and rhetoricians? As a provocative cultural reorientation, we might liken it to Bob Dylan and Kendrick Lamar earning Nobel Prizes in Literature — it no doubt shook up Athenians’ concepts of who and what could count as purveyors of culture and wisdom.

For Socrates, the Oracle’s decree was a vindication of his belief in the wisdom of not-knowing. While the Sophists charged exorbitant rates to impart knowledge to their well-sandaled clients, Socrates held court on the street, making his name by gently yet brilliantly questioning the very foundations of Greek knowledge. He did so not by knowing more than his audience, but by claiming to know less. “One thing only I know’, he famously said, “and that is that I know nothing.”

The Socratic method provides a counterpoint to, and warning against, the dangers of over-knowing and under-thinking. Sadly, still today, “learning” consists largely of memorizing and repeating static definitions, much as the Sophists were doing two thousand years ago.

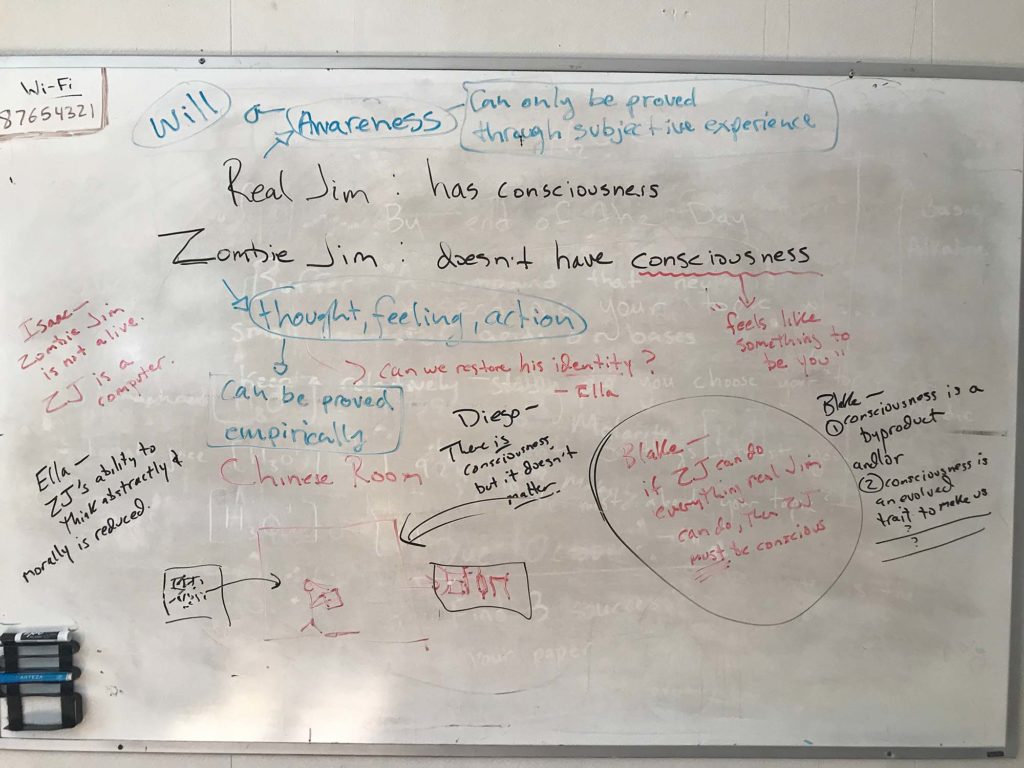

To truly think for ourselves, and to teach our students to do so, we first need to abandon the notion that the smartest person in the room is the one who recites the most facts or has read the most books (or Internet posts). At Qualia, we design lessons to “go for the intellectual jugular,” to bring out the deepest and most fundamental questions about a topic, and guide the students in how to productively explore, parse, and play with such questions. In our seminars, the smartest kid is the first one to stop citing book and internet knowledge and simply say, “Wow, that’s a hard question!”, kicking off a rollicking, playful discussion full of light bulb moments and deep reflection.

The Greeks had a word — aporia — for the mental state created by such epiphanies. Each year I look forward to working with our teachers to encourage aporia moments and teach students the value of a “beginner’s mind” approach to learning. As we settle into what promises to be another extraordinary school year, I encourage you to ask your children about their aporia moments, and to make not-knowing and deep inquiry part of your family’s discourse and culture.

Yours in transformative learning and teaching,

Jim Hahn

Founder and Educational Alchemist

Focus Friday

In addition to our seniors receiving some valuable college counseling information, the school participated in a day of Camp Games that began with some exercises to help learn names. It’s not easy to remember names and faces when we only see 1/3 of everyone’s faces daily. Thank you to Michelle Ratliff for devising fun ways for us to get to know each other!